|

VANCOUVER BROADCASTERS

As their graduate years in the English Department at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, B.C. came to an end, Jeff Groberman grew wary about the practical utility of his shift from Geophysics to English Lit. One day, as the April showers of 1971 pelted Arthur Erickson’s academic quadrangle, Groberman approached his pal Colin 'D.T.' Yardley with a murky proposition. "You realize," he began, "that with M.A.’s in English Lit, there are two things we can do in life. Teach or eventually end up slogging logs in a pulp mill." D.T., who had already spent two summers working at the Harmac Pulp Mill near Nanaimo on British Columbia’s Vancouver Island, was noticeably depressed. There was no way he wanted to spend the rest of his life teaching. It struck him as odd that up until this moment, he had never even thought about what he wanted to spend the rest of his life doing. Jeff Groberman had a suggestion ready to hand. "You and I like humour. We liked doing funny shit, right? And writing funny shit." This was true. Yardley recalled how difficult it was for him to write a serious essay or term paper on any topic without watching as, often against his will, humour just kind of took over and turned a paper on ‘Gender Inequities In The Prose of Henry Miller’ into ‘Women, Animals and Ghosts in American Literature.’ "So what did you have in mind, Jeff?" Yardley sighed and looked out the SFU cafeteria window at the passing students, most of them probably science majors who had high paying stable careers already mapped out, complete with SUVs and a cabin up at Bunsen Lake. "Have you ever listened to the comedy on CBC radio?" asked Jeff.

This, remember, was

Vancouver, Canada 1971 – a place and time long before aspiring Hollywood

North media writers required agents and endured endless runarounds,

delays and rejections in a field so jammed with competitors that

teaching English in a pulp mill would be an attractive alternative. Jeff

made an appointment with Frank Stalley, a CBC radio variety program

director, who occupied one of the many CBC radio offices then squirreled

away in the labyrinthine recesses of the Hotel Vancouver. In the

years to come, as Dr. Bundolo went national on CBC radio and then on to

television, its creators would deal with many program directors – none

as supportive and well meaning as Frank Stalley. In the days leading up to their appointment,

Groberman, Yardley and friend, Tom Poulton, met in Yardley’s apartment at the SFU

student residences and started making comedy. Equipped only with a cheap

audiocassette recorder, with a built-in condenser mike, they read their material onto

tape. Some

wise person once wrote that if you do what you love, good things will

follow. That first afternoon left three young university students

drenched with

perspiration and laughed out on the floor of the apartment. As

Yardley would later

attest, "That day we discovered the joy of free form creativity. We

could

concoct scenarios as absurd, bizarre, gross or outrageous as we

wanted – and there

was no one to say that we couldn’t, or that we were wrong,

politically incorrect, out

of line, being silly or whatever. We just went for it and got

delirious finding

voice for thoughts that conventional wisdom and morality had long

silenced for most of

us." Groberman would add, "Most of the stuff we came up with that day we would never use

– certainly not on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation – it was just too out

there. And we weren’t smoking anything. This was beyond smoke." In the cold light of morning, they realized that there was precious little on the tape

that they could take downtown to the CBC and present to serious people with creases in

their pants. But Groberman would not be deterred. He was a man on a mission to

get their comedy inserted somewhere in the schedule of CBC radio. Poulton dropped

out of the effort for reasons never stated and Yardley hung in, but in the end it was Jeff

Groberman and he alone who did the necessary foot slogging, door knocking, phone calling

drudge work to make sure the CBC could not ignore these gnats who kept showing up,

satchels stuffed with comedy scripts. Stalley finally gave them a shot. He had read their material and had ‘found it pretty funny.’ He would give them a small slot in CBC Vancouver’s four to six PM afternoon show hosted by Patrick Munro. They would have a three to five minute hole to fill with their comedy.

Drama and

classical

music? Was this really the right guy to produce their

comedy? Jeff and Colin had doubts, but they were soon

dispelled. Kowalchuk turned out to be an eminently intelligent, affable

guy, a painstakingly thorough and professional producer and a comedy

editor par excellence. Of course, in the beginning, it was all brand new

territory for the three of them. Put together, they had a grand total

of zero minutes and zero hours of broadcast comedy under their belts. In the summer of 1971, Kowalchuk held auditions in the bowels of the CBC studios, then located in the Hotel Vancouver somewhere between the mezzanine and the public toilets. Many aspiring actors read their way through sketches featuring the moralizing nit, Trashman, and his sidekick, Ban Tobacco, pollution fighters extraordinaire. There were parodies of Canadian political figures and silliness that involved chickens, Republicans, morphodites (sic) and greasers all verbally duking it out in an aural tapestry that scorned such boring nonsense as cause and effect, logic or beginning, middle and end.

Vancouver actors Ted Stidder and Bill Buck

impressed in the auditions. Stidder was a seasoned stage actor with a

gruff delivery

that made him a terrific comic crank; slipping into brusque sarcasm

at the drop of a bad

pun. Buck was a comic anomaly. A conservative, nattily groomed nice

guy, Buck

lived with his mom until he was about fifty, but no one seemed to

notice at the time. Bill Buck, in all his Dudley Dooright, cleancut

Canadian square niceness, would

prove vital to the chemistry of the full fledged Bundolo group which

would be dominated by

two extraordinary comic performers, Bill Reiter and Norm Grohmann.

But more about

them later – they had not yet arrived on the scene. Late in the audition process, two performers emerged who would become mainstays of the

show’s weekly network presence – the novice Marla Gropper and seasoned pro Steve

Woodman. Marla, a personal friend of Groberman, had never acted before, but wanted

to and was dynamite right out of the gate. Her natural ease in front of the

microphone belied her lack of experience. Her comic timing and voice modulations

were exceptional, and her flexibility in playing characters of many ethnic persuasions

across many age groupings made her a shoo-in for the female role in the otherwise all male

cast. Steve Woodman knocked everyone out. A living, breathing incarnation of

the colourful AM radio personality, Woodman came to life in his voice characterizations

and roamed there like a mad aural imp. A lesser version of himself (and there are

thousands of them, AM morning show Rock Jocks all) would have put you off as smarmy,

plastic and prefabricated. But Woodman had something deeper going in his snappy

patter. He parodied himself with gusto. In addition to dynamite voice control

and spot-on delivery at the microphone, Steve displayed hints of comic genius and

displayed them often. He lifted characters off the page in ways that surprised

Kowalchuk and the prank boys and completely surpassed their expectations. When the

audition dust had settled, Woodman was their star, until, of course, Reiter and Grohmann

came along. But more about them later.

Yardley recalls, "I was twenty-three years

old, sitting in a car with my dad at the side of the highway near Fairmont Hotsprings,

B.C. in the East Kootenays when the very first episode of Kreegah Bundolo Express

played over the radio. My heart pounded. You know, it must’ve been how

Spielberg felt when he first played E.T. for his mom (wink). A whole three-minute

radio piece, wild and corny as hell and the buttons were popping off my chest. My

dad was proud of me and diplomatically hinted that – ahem – we had some way to

go before we would make people forget Wayne and Shuster." With respect to the

name, Jeff reflected, "Maybe we were Edgar Rice Burroughs buffs. Kreegah

Bundolo is what Tarzan used to yell at gorillas or maybe gorillas

yelled it at him. Who knows for sure? At any rate, we liked the

rhythm of it and it stuck." There

had been comedy drop-in pieces on regional radio before, but for the

most part, they were squeaky clean, middle-of-the-road offerings typical

of the CBC up to the early seventies. And most of those programs

never went anywhere. Kreegah Bundolo Express was different.

It grew organically out of the west coast milieu about the same time a

group called Monty Python’s Flying Circus was fashioning their hugely

successful absurdist vision in Britain and a full two years before the

Royal Canadian Air Farce would take to the airwaves with a show that

closely copied the Bundolo format. Response to the Bundolo

drop-ins grew exponentially. Something began to stir in the

catacomb offices in the Hotel Vancouver; a buzz about this goofy little

comedy thing on the west coast – a buzz heard 3,000 miles away in CBC

head office in Toronto, Ontario. October

4, 1972 was a chilly night on the campus of the University of British

Columbia. Don Kowalchuk had rented the Music Building

Recital Hall to launch the first public recording of a new CBC network

radio comedy. "I

remember when Jeff called," said Yardley. "Kowalchuk had told him that

on the strength of numbers, growing listener support and fan mail for

our comedy drop-ins, the CBC was going to give us a shot at doing a

pilot for a full network half hour show, to be produced in front of a

live audience at UBC. A live audience! Yikes. No more hiding

in a studio convincing ourselves we were funny. It was acid test

time. Prove it in front of a live audience." A few

days before that first taping, Frank Stalley bumped into Groberman in an

elevator at the Hotel Van. "I understand your program is getting off

the ground," he said with a smile. "It’s taxiing down the runway,

F.S.," said Groberman, who always managed to sound like Groucho Marx on

benzedrine when he said such things. Intense, Jewish, black curly

hair and mobile eyebrows, there was something about Jeff that shouted

that Groucho was, in fact, his spiritual forefather. Kowalchuk,

displaying a prescience remarkable for a producer who had never worked

on anything other than classical music and drama, conceived that the

Bundolo show would work best if it combined three essential elements on

stage – the performers, a live band and an onstage sound effects

technician, a dandy named Lars Eastholme. Nothing canned or

pre-recorded, everything would be seat-of-the-pants live to tape

broadcasting; a show pounded together on the fly and made more

spontaneous and exciting for it – hopefully. The

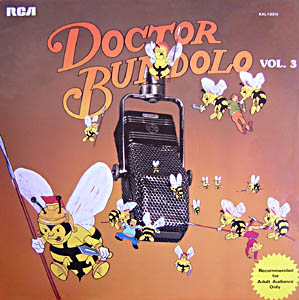

full name for the half hour series was to be Dr. Bundolo’s Pandemonium

Medicine Show. It came about during a marathon session in which

Kowalchuk, Groberman and Yardley tossed around whole lists of possible

titles, finally deciding that if ‘Bundolo’ meant ‘gorilla’ in Swahili,

(It did, didn’t it?), then a gorilla with a Ph.D., i.e., Dr. Bundolo,

captured something of the oxymoronic that would certainly make them

whoop in Red Deer – a then small hamlet south of Edmonton in the

next-door province of Alberta. The

show slowly built an audience across Canada in its weekly half hour AM

time slot. A few shows into its run and knowing that

Ted Stidder would be leaving the cast, Kowalchuk and the writers

auditioned for a replacement. They were stunned by the comic

brilliance of a young Vancouver actor named Bill Reiter. A big

jolly bear of a man, often sporting a mountain man beard, born in

Verdun, Quebec, Reiter had grown up in Vancouver's equally tough East

End and brought a street smart irreverence to comedy that was so

in-your-face funny that he quickly became the star as well as the brunt

of most of the humour on the show and gave back as good or better than

he got. But he would be challenged. In 1974, Yardley and

Groberman started bugging Kowalchuk about this guy named Norm Grohmann

who did the weather report on BCTV. Around this same time, Steve

Woodman, while coming home late at night from hosting a Variety Club

Tele-thon, suffered a tragic car accident that effectively ended his

radio career. Grohmann auditioned and won a role in the cast

in a walk. For the next seven years, Bill Reiter and Norm Grohmann, more than ably assisted by Marla, and with the great X Factor chemistry that Buck added, would be the cast of Dr. Bundolo's Pandemonium Medicine Show, a weekly half hour of comic mayhem and post-Freudian ersatz that would trouble the atmosphere more than the US government's HAARP project in Alaska (Google it). If the scripts were occasionally well written, they were often lifted into the realm of inspired comedy by the scintillating improvisational humour that both Reiter and Grohmann brought to the stage – usually, the stage of the Student Union Building at the University of British Columbia. The SUB theatre often overflowed its 700-seat capacity for Bundolo shows, with standing room and students sitting in the aisles, it was often comic bedlam. Over time, Reiter became the big jolly guy that every loyal student fan had to get a piece of, even to the extreme of bombarding him relentlessly with paper airplanes while he was trying to address the hallowed microphone of the Canadian mother corp. Many of Reiter's impromptu grunts, woofs and groans, kept in the show, are, in fact, his reactions to getting nailed in sensitive body parts with a Boeing Cruizer designed by some UBC engineering student. From

1972 to 1981, and for a brief reprise during Expo '86, Dr. Bundolo's

Pandemonium Medicine Show established itself as the wildest, most

spontaneous ensemble radio comedy ever to arise in the Canadian west. Dr. Bundolo was hugely popular during the 1970’s in Canada. In some

respects, it belongs to a well-represented tradition of Canadian

satirical humour that includes Wayne and Shuster, Codco, The Royal

Canadian Air Farce and This Hour Has 22 Minutes. Of this family of

shows, Bundolo was perhaps the black sheep; the show least likely to

conform to expectations and most likely to bend the rules into pretzels

and serve them with green beer. There was something decidedly west

coast about Bundolo; something that didn’t always sit well with the

more button-down sensibilities of central Canada. If Berkeley is

to Boston as Vancouver is to Toronto, we are talking cultural

differences of no small magnitude. Bundolo was the wild, unkempt,

dope smoking hippie relative out in Lotus Land. Maybe entertaining

as hell in small doses, but you sure wouldn’t want him hanging around,

sleeping on your sofa or chatting up your sister. A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I/J | K | L Mac | Mc | M | N/O | P/Q | R | S | T/U | V-Z

|